Empirical research assumes that the relationship between inequality and economic development stays the same no matter where a country is on the inequality scale, as measured by the Gini coefficient (which ranges from zero, when everyone has the same income, to 100, when a single individual receives all the income).

In two recent papers—Inequality Overhang and Inequality and Growth: A Heterogeneous Approach—we dig deeper into the direction of this relationship, using a sample of 77 countries at different stages of development and representing all geographical regions, with at least 20 years of data, and employing techniques that address some shortcomings in the literature. Owing to data limitations, we focus on income inequality only and refrain from analyzing the equally relevant concept of wealth inequality.

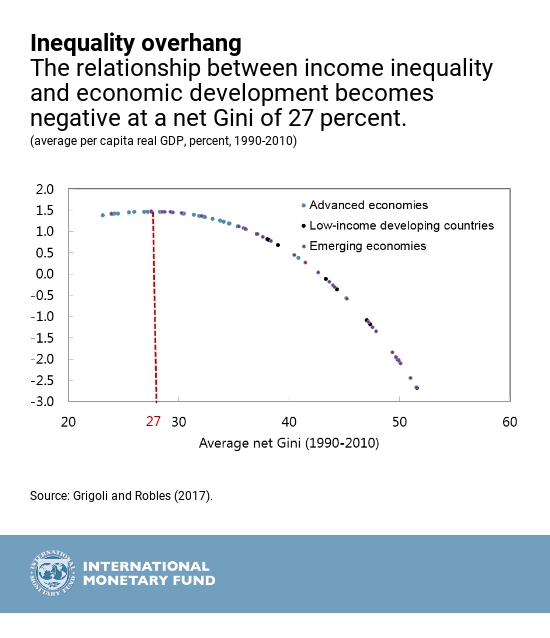

What we find is that the effect of income inequality on economic growth can be either positive or negative, and that at a particular level of inequality—at a Gini of about 2.7 percent to be exact—the direction of the relationship changes—that is, where inequality begins to hurt economic development.

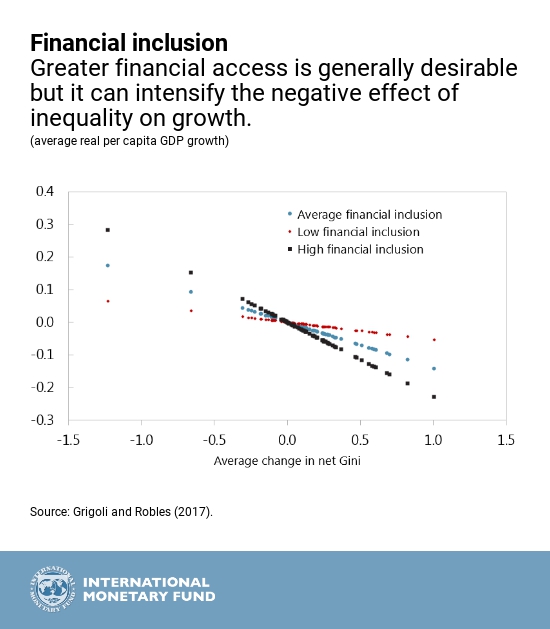

We also assess if some of the commonly proposed tools to combat the harmful effects of rising inequality—such as boosting financial inclusion and promoting female labor participation—effectively mitigate the impact on economic development.

Not all countries are alike

Our results show that a change in income inequality growth does not have the same effect across countries. While the median impact of inequality growth on per capita GDP growth is negative and significant, lasting about 2 years, this is not true for all countries. In Ecuador, Jordan, Nigeria, and Panama, for example, the effect is large and negative.

For other countries, like Finland, for instance, the impact is positive, as the results for the 25th percentile show. This large dispersion highlights the limited relevance of the average effect typically estimated.

Inequality overhang

Different effects across countries can be linked to different initial inequality levels. If income is not highly concentrated, an increase in inequality can provide incentives for countries to be more productive. If highly concentrated, that same increase can lead to rent-seeking behaviors—the top appropriating a larger and larger share of the nation’s pie for themselves. Also, when inequality is low, it is unlikely that any increase would lead to social unrest; conversely, when inequality is already high, any further increase would likely reduce social consensus, and the ability to implement pro-growth reforms.

The chart below highlights the existence of a hump-shaped relationship between inequality and economic development, revealing the existence of what we call an “inequality overhang.”

In other words, the impact of income inequality on economic development is positive for values of a net Gini below 2.7 percent (where net refers to its measurement after taxes and transfers), but the impact becomes negative for values above 2.7 percent. Also, as countries become more unequal, the negative impact on economic development becomes larger.

Trade-offs and win-win policies

Improving access of households and business to banking services, as well as promoting participation of women in the labor force can help combat the negative impact of increasing inequality on economic growth. However, they could also make things worse by over-leveraging poorer households or generating an oversupply of labor .

.

We find that, while financial access is generally desirable, it can lead to a greater negative impact of income inequality on economic development, as banks may curtail credit to customers at the lower end of the income distribution because of their inability to repay. To prevent this trade-off, mechanisms should be considered to ensure that those who lose access to credit when income becomes more concentrated can continue consuming even when their income falls. On the other hand, greater female labor participation is a win-win in that it enlarges the pool of talent that is available to work and reduces (or even reverse) the negative impact of inequality on growth.

Grigoli (IMF)

No comments:

Post a Comment