"Chapman goes on to explain how autistic people can be distinguished from neurotypical people through the comparison of clusters of psychological characteristics and how they are treated by society at large. Autistic people are defined not by a fixed set of bioessentialist traits with natural unity, but by fluid characteristics that are contingent upon the social context.

“[Autistic clusters] have no natural unity but … are unified with respect to their contingently perceived positive economic or social utility, as well as their relationship to external structures and norms.”

That is to say: socially and economically useful psychological and behavioural clusters of characteristics that are supported by external structures and norms define neurotypicality; whilst a fluid set of socially and economically ‘un-useful’ psychological and behavioural clusters of characteristics that are unsupported by external structures and norms define autism.

ADHD has another pathologised and unsupported cluster of psychological and behavioural characteristics which are distinct-from but overlapping-with autistic psychological and behavioural clusters – and I would warrant that other neurodivergencies inhabit similar distinct-but-overlapping positions.

The division of humanity according to social and economic utility occurs within a society that values people in accordance with their social and economic utility, augmented by an economic model that requires (and recursively supports) a particular range of human characteristics and social norms. These conditions exist within the neoliberal capitalist economic and social framework.

As Byung-Chul Han argues in ‘Psychopolitics’, people are now expected (in service of capital) to auto-exploit through self-optimisation; marketing themselves dishonestly, exhibiting constant personal growth, acting with hypersociality, and compulsively achieving. We become our own panopticons – constantly observing and enforcing self-exploitation for the benefit of capital.

“The body no longer represents a central force of production, as it formerly did in biopolitical disciplinary society. Now, productivity is not to be enhanced by overcoming physical resistance so much as by optimising psychic or mental processes. Physical discipline has given way to mental optimisation“ (pg 25).

At this moment in history, in the society that I live within, neurotypical people are those who exhibit clusters of psychological and behavioural characteristics that enable more frictionless mental optimisation in accordance with psychopolitical capitalism; and conversely, autistic people are those who exhibit a set of clustered psychological and behavioural characteristics which make mental optimisation and self-exploitation more difficult. Neither group exists in a bioessentialist way; both are contingent on material social and economic conditions in any given time and place, and at the present moment, referent to the self-exploiting human''.

"The reality of autism: On the metaphysics of disorder and diversity’ had a big impact upon me during a period of great confusion and self-doubt for me.

How do you conceptualise autism? Do you agree with my conclusion, or is there a logical error somewhere? Do we need to move beyond the concept completely - is it too stained?

"I self-diagnosed as autistic...Isolation and withdrawal ensued, on a global scale in the form of lockdowns and border closures, and personally as I suddenly found myself with a new identity that simultaneously felt welcoming and isolating.

I left my part time project coordinator position at a small non-hierarchical charity, feeling unable to maintain connections made by my heavily masked former self. I stopped using telephones to escape the discomfort that they brought (bring) me, and I refused to appear on video calls. For months the only social contact I had was with my partner. I experienced a kind of social death that felt inextricably linked to ‘being autistic’. Autism felt like a state of separation, defined by the absence of social relations and connection to the society around me.

The academic and social discourse around autism contributed to this sensation. I had read all about it — it’s how I self-diagnosed. Psychological, psychiatric, and psychoanalytical theories felt like observations made from the outside by self-interested and arrogant observers (eg Baron-Cohen). I learned that there were no biomarkers for autism and attempts to identify specific genetic code related to autism seem doomed to fail (Fletcher-Watson and Happe, 2019).

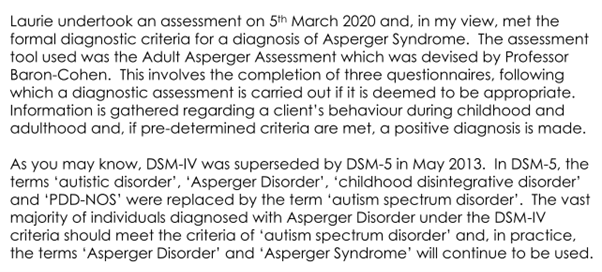

Obtaining a diagnosis felt like living the discourse. I had to become the observed medical subject. It was a painful experience that didn’t give me the position to inhabit within society that I hoped it might. The trained professional sitting opposite me asking binary questions designed by the aforementioned Simon Baron-Cohen, fumbling with clumsy linguistic attempts to translate my mindbody, seemed to have very little understanding of my experience''.

"I second guessed myself the whole way — had I created this diagnosis through my own desire for belonging and identity? Was I just answering the questions the way I thought they wanted me to answer them in order to receive what I wanted from them? I answered as truthfully as possible and received a letter and a report that stated I was a disordered human being. And not much more. Reading between the lines, the message was: ‘help yourself if you can — but you probably can’t because you’re autistic.’

Extract from the cover letter of my diagnostic report

I instinctively rejected the notion of functioning labels. Claiming to be ‘high functioning’ felt like an attempt to align oneself with the ‘undisordered’ as much as possible, making a distinction between more-human and less-human types of autistic people. It seemed like attempted conformity and self-subjugation at the expense of solidarity and collective liberation. I read about the history of autism; how it is tied up with eugenics, the holocaust, and the harmful medicalisation of natural human bodies (see ‘Asperger’s Children’ and ‘The Kaiser’s Holocaust’ for example).''

Laurie Green

No comments:

Post a Comment